Why nuclear push could be sweet music for City

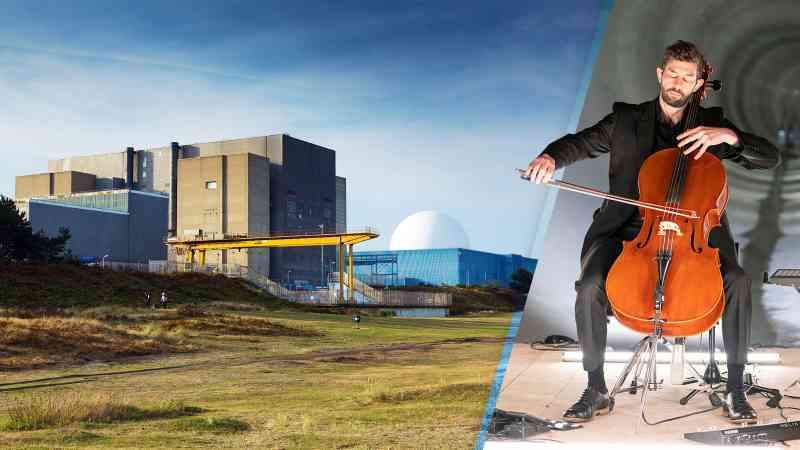

Flanked by arty strip lights and with a minimalist keyboard at his side, the composer Rob Lewis paused before putting bow to his cello. This was the maiden performance of a new piece, not in a concert hall but 70 metres beneath the streets of London.

Lewis had written a nine-minute work to mark completion of tunnelling on the Thames Tideway, a 16-mile long, 24ft-wide pipe that will capture the run-off from the capital’s sewers when they overflow with rain. Fittingly enough, he performed last month in one of the underground chambers, the music echoing eerily from the tunnel walls.

In the streets above where Lewis played, City institutions have been taking a keen interest in the Tideway’s progress and not because they are avant-garde music buffs. Investors are intrigued by the novel way the £4.2 billion project was financed. The method has been seized on by the government to kick-start a £100 billion-plus splurge on new nuclear power stations, a move that could create a giant new market in infrastructure investment.

The not-so-magic ingredient is asking customers to pay more up front and to guarantee payments in the future. Kwasi Kwarteng, the business secretary, said the plan would have a “small effect” on bills but did not say by how much they would go up. Industry experts think each large new station — and the plan envisages as many as eight — would add between £6-£10 to the average household bill.

The buffer of cash raised from customers can be used to hammer out problems with power plant designs, and can be eaten into if construction proves troublesome. The project company is also allowed to continue to charge customers once the station is working, with the amount based on the value of the project. The whole arrangement is monitored by an independent regulator, hence its name: regulated asset base (RAB) financing. As a condition of the licence, investors in the project company are on the hook for a pre-agreed level of cost overruns.

The buffer and continuing flow of income provide sufficient comfort for institutional investors, who would normally run a mile from the risks associated with new nuclear projects, to lend money. This dramatically lowers the overall interest rate on the debt required. The Department for Business claims the reduction in interest payments could save consumers £30 billion over the life of a new power station.

“In essence it is reducing the cost of capital by cutting back the construction risk to investors,” Richard Goodfellow, head of infrastructure, projects and energy at the City law firm Addleshaw Goddard, said. Some energy experts, however, are sceptical that the promised tidal wave of investment will ever materialise. “There is no cheap or easy way to do new nuclear,” Simon Cran-McGreehin, head of analysis at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), said. “I fear the government’s big ambitions will prove a distraction that won’t ultimately lead to much.”

The need for a new super-sewer for London was recognised more than two decades ago but work only began in 2016. It is not being built, as many assume, by Thames Water, but by a specially created company that has its own licence from the industry regulator Ofwat. Bazalgette Tunnel (named after Sir Joseph Bazalgette, the Victorian engineer who built London’s first large sewers) uses the licence to put a surcharge on Thames Water bills: £21 a year, with the right to increase it to £25.

This guaranteed stream of money has allowed the investors in Bazalgette — the insurer Allianz, Amber Infrastructure, Dalmore Capital and DIF Capital Partners — to issue £1.8 billion worth of bonds to cover part of the cost and to pocket a solid dividend stream.

Ireland used an upfront levy on customer bills to help fund the Gas to the West project, under which 200km of pipeline was built to connect regional towns to the national gas network.

Boris Johnson now wants to use the method to increase the number of nuclear power stations in the UK and the rate at which they are built — an acceleration to “warp speed”, as he told industry leaders at a No 10 summit on March 21. Instead of one a decade, or none at all, as has been the case for most of the past 40 years, Johnson eventually wants one a year, with eight new power plants envisioned in the medium term.

One is already under construction at Hinkley Point in Somerset. It is being built by the French utility company EDF and did not use the RAB model. Instead EDF and its partners took on the risk of the whole project. After lengthy negotiations, the government agreed in 2016 to pay £92.50 a megawatt-hour for the electricity it will eventually generate, a hefty premium to the then prevailing rate of £50. The National Audit Office was critical, saying that the arrangement “locked consumers into a risky and expensive project with uncertain strategic and economic benefits”, but stopped short of saying it represented bad value for money, concluding that that would not be known “for decades”.

Since Johnson threw his weight behind the RAB route, the government has quickly put in place some necessary stepping stones. Four days after the nuclear summit at Downing Street, the Department for Business quietly published the criteria that projects would have to meet.

First up is likely to be a new plant planned for Sizewell on the Suffolk coast. There are already two nuclear stations there; one, Sizewell A, stopped generation in 2006, while the other, Sizewell B, started operations in 1995. The third, Sizewell C, which faces stiff opposition from some local groups, would be a copy of the Hinkley Point plant.

It will not, though, be built by EDF. Instead a new company will be created, with EDF and the government owning minority stakes. The remainder of the shares will be owned by infrastructure investors; similar players, industry experts suggest, to the ones that invested in Thames Tideway. If the company succeeds in winning a licence, it will have the power to put a levy on electricity bills. When the project is judged sufficiently advanced, the new company will issue several billion pounds’ worth of bonds to fund construction. “RAB is the right model for financing Sizewell C as it will lower the cost of capital and deliver significant savings for consumers,” an EDF spokesman said.

Ministers are hoping that big British pension funds will buy the bonds and have helped to clear the way with reforms to the EU’s Solvency II regime, which at present limits the type of investments that insurers can hold.

Goddard sees groups with a record of investing in infrastructure projects — Canadian pension funds, for example — as the biggest players. “I would expect the bulk of the investment — perhaps two-thirds — to come from the big global infrastructure funds that are already big investors in UK assets,” he said. “There are some investors who will be put off — either because of the size of the projects, the timescales, or just because it is nuclear.”

Eoin Murray, head of investment at the fund manager Federated Hermes, agrees that some will not want to get involved. “Nuclear is an emotional subject — this is the one area in which you really get a big split between institutions,” he said. “You could gift-wrap it completely and it wouldn’t make any difference at all to some investors.”

After Sizewell, the pipeline of projects is unclear. Ministers are keen to push ahead with the on-again, off-again scheme for a new station at Wylfa on Anglesey. Hitachi, the Japanese industrial group, was to have built two new reactors there, but the project has now been taken up by the US engineering giant Bechtel. Senior sources at EDF say it is also casting a covetous eye over Wylfa as the possible site for another Hinkley Point design. There have also been discussions on a new plant at Moorside, close to the Sellafield nuclear site in Cumbria.

RAB financing could also be adopted for a new type of small reactor. Rolls-Royce, which builds the power plants for nuclear submarines, has submitted a design to Britain’s nuclear regulators, while two US providers, Last Energy and TerraPower, are also weighing options in the UK.

Cran-McGreehin says one danger of the RAB model is that it transfers risk to bill-payers rather than the companies building the station. His bigger query, however, is whether there is too much concentration on nuclear. “Governments do from time to time get very excited about nuclear, then cool off,” he said. “I am not convinced all this will actually come to pass, and in the meantime it risks taking the focus away from investment in renewable energy.”

Nuclear industry sources defend the model, saying that bill-payers — and taxpayers — will in the end have to pay for new sources of energy regardless of type. The National Audit Office report into the financing of Hinkley C says that it will put £10-£15 on the average power bill until 2030, even though all the risk was ostensibly transferred to EDF and its partners.

“It is definitely the right thing to try and cut the cost of capital, otherwise the interest bill just becomes a tax on energy,” a seasoned energy industry executive said.

“The key thing in making it work is that the regulator makes absolutely sure the design and construction plans are rock solid before giving approval and you don’t end up just shifting the problem onto bill-payers.”

Post Comment